Karen Cheney - Visual Ecologist

Dr. Karen Cheney is a visual ecologist based at the University of Queensland, Brisbane. She uses a multidisciplinary approach to understand how animals perceive their world. She is particularly interested in the function and evolution of animal colour patterns in marine organisms, such as the colourful displays of coral reef fish, and aims to understand why animals have such diverse visual systems. She was recently awarded a Future Fellowship from the Australian Research Council to study fish like seahorses and toxic boxfish that have potentially ‘super-human’ colour vision systems. These species may process colour using 4 or 5 spectral channels, instead of our 3. Outside of work, Karen has a busy family life raising 3 children, and enjoys reading, and when possible skiing and sailing.

Animals use complex colour patterns as camouflage or as signals of deadliness or sexiness to predators or mates. Yet it’s still not well known how many animals process highly contrasting colours, or even tell certain colours apart. To address this gap, Karen studies colour vision, mimicry, chemical defence, and colour change in a variety of fish species—which you can read about on her website here.

Amanda: Thank you for chatting with us, Karen! What do you think brought you to this kind of science?

Karen: Growing up, I had an affinity to water. I swam competitively for England throughout my high school years, and then later moved my passion for the water to SCUBA diving and sailing. When I was looking for a PhD, I knew I wanted to conduct marine-related research, but at the time didn’t know in which direction this fascination with the underwater world would take me. I think most research career paths are shaped by what ignites your passion and interests, but also by what doors are opened for you, or by you, along the way.

In terms of researching colour patterns and colour vision, my interest was ignited when I was conducting behavioural observations on cleaner wrasse, which are fish that remove parasites from larger coral reef fish. I became aware of two species of mimic reef fish that were in the area, which were using a colourful pattern as a disguise to fool the surrounding reef fish into thinking they were also cleaner fish. One species, Aspidontus taeniatus, looks so similar to the cleaner wrasse that it still takes me a good 5 minutes of observing it swimming to determine whether it’s a mimic or not. The second species, Plagiotremus rhinorhynchos, I noticed had the ability to change colour to either mimic a juvenile cleaner wrasse, which has a black body and neon blue stripe, or an orange body, which it used to hide in schools of orange fish. They have large fangs and attack unsuspecting reef fish to feed on scales and pieces of fin and therefore use their colour patterns to prevent being detected.

A: What do you love most about your work?

K: I love learning about the behaviour of animals, and trying to unlock the meaning of how they communicate through colour and pattern. I enjoy fieldwork, in particular trips to the spectacular Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef, and being underwater watching fish. I find that spending time underwater clears my mind and makes me think about our research questions in new ways. Finally, I enjoy seeing students grow and develop their knowledge and skills to become excellent research scientists.

A: What’s your normal workday like?

K: If I’m not conducting fieldwork, I come into work and usually first check on the fish that we keep in our aquarium. We currently have seahorses, triggerfish, clownfish and damselfish so they are a diverse community and mostly always waiting for a feed. I then head to my office and spend most of the day meeting with students and helping them to conduct their research, reading drafts of papers by our research group and collaborators, analysing data, peer reviewing papers, editorial responsibilities, coordinating and teaching undergraduate courses, and administration work, including managing grants.

In my early career, I’d spend months at time in the field, but my travel became limited once I had a family. I go to the Great Barrier Reef at least once a year, but also do some shorter diving trips around Brisbane to collect samples. Many of our experiments are conducted in aquarium facilities at UQ. In the field, we spend the first week or so catching fish with hand and barrier nets, setting up tanks for the fish and then training them to conduct behavioural experiments to test how they are perceive different colours and patterns.

A: What are the biggest surprises (for better or worse) that you’ve experienced as a scientist over your career?

K: My research focusses on the perception of colour by fish and other animals. Visual perception can only be reliably tested using behavioural experiments, which are often challenging as we’re asking the fish to do a variety of tasks (for example, peck at a coloured dot) to receive a food reward. When we do such experiments, I am continually amazed at the different personalities of fish within the same species. Perhaps it is not that surprising as we see large personality differences in humans, and in our cats and dogs, but fish are also so variable. When we conduct behavioural experiments, we have fish that are slow and steady, think carefully about their decisions, and do the task we give them accurately. Then others that rush in and do the task as quickly as possible without really thinking, making a large amount of errors along the way.

Although I am familiar with this now, one thing that I was perhaps not prepared for was how competitive science is and that funding is very limited. I’ve seen many fantastic scientists leave the field as they’ve been unable to secure new positions or find funding for their research. Support for parents and carers seems to be improving in some areas, but I know of many scientists who have changed profession as they struggle to continue research after career breaks.

With young children, it’s been challenging to strike a suitable family-work balance. Now that my children are older it’s getting easier, but I used to feel that my family life and work life was just a huge overlapping list of tasks that needed to be done - there was very little separation between the two.

A: What are some of the strangest things you've seen/heard/experienced in your job?

K: I’ve seen some amazing things underwater, including schools of hammerhead sharks, a pod of playing dolphins, and coming face to face with octopus trying to grab my camera. However, the weirdest thing are remoras, also known as suckerfish, trying to attach to my leg or stomach while I’m watching or catching fish on SCUBA. They have flat heads with a sucker-like organ that creates suction to take a firm hold of your skin. It is such a very strange and unpleasant experience!

Also researchers licking poisonous animals to feel the effects of their toxins—or, in one case, the researcher got a poison-fang blenny to bite them in the leg. This was a while ago, and wouldn’t be allowed today.

I had a fish parasite named after me, Pseudobacciger cheneyae, after I collected some damselfish for a colleague, and they were heavily infested with an unknown species!

Karen is happy to chat more about her research or career as a visual ecologist. She can be reached by email here.

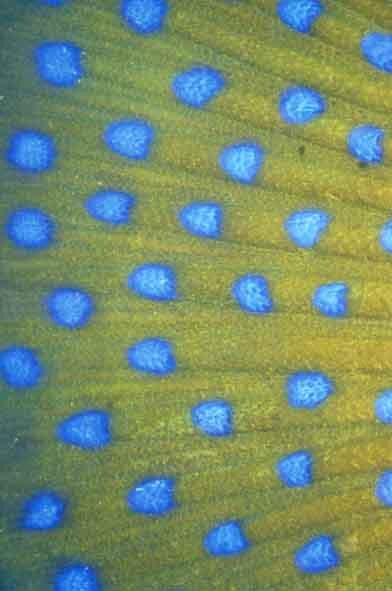

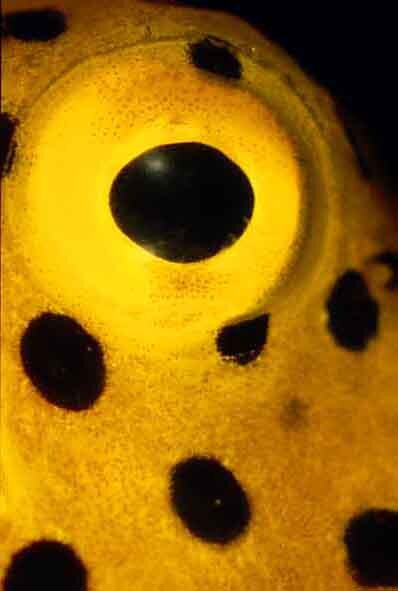

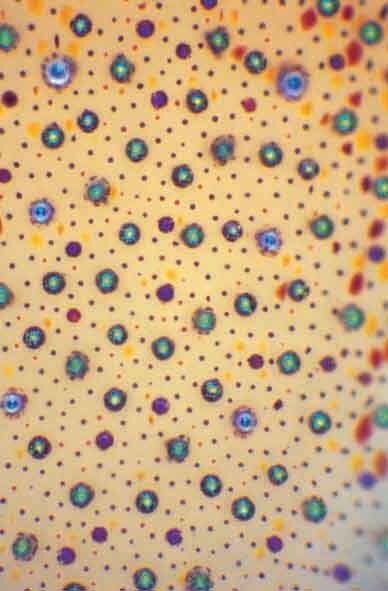

Fish colours and fish eyes. Photos by Prof Justin Marshall

Writing prompts:

Write a scene in which your narrator is watching fish—in captivity or nature—and notices differences in their behaviour (movement, feeding, etc). How does this observation reflect a conflict in the narrator’s own life? Does it help them understand the situation in a new way?

Let an experience with fish—in captivity or nature—affect the way your narrator experiences or defines certain colours. For example, let ‘gold’ become irrevocably linked with the colour of a particular fish, or use the fish itself to create a new name for (or way of describing) the colour ‘blue’. Be specific about the type of fish and its environment. See also Werner’s Nomenclature, here.

Write a scene in which your narrator is a visual ecologist or meets one at a dinner party, cafe, school drop-off, park, gym, hike, nightclub, etc. What might ‘visual ecology’ mean in that particular context? For example, how does your narrator relate to the idea of colour in attraction of mates, anti-predator warning, or camouflage? How might the idea of colour manipulation/communication connect with your narrator’s desires, conflicts, or actions?

From L to R: Karen’s research group - Team Fish - including her students and kids; Karen and her daughter in the field; Team Fish on the water; and a very enviable research site

Karen recommends:

Science Write Now is a Booktopia affiliate, meaning that we earn a small commission—at no cost to you—for books purchased through links in our website. We feed these funds straight back into our budget to pay more writers and build more website content for you! Thanks again for supporting us!